Comfort in hospital spaces

In 1858, Florence Nightingale expressed the following words: ‘Unnecessary noise is the most cruel absence of care which can be inflicted upon either the sick or well!’ Today, more than 100 years after, research shows that we are still struggling with noise wherever people live, work, sleep and recover.

Urban noise

Dr. Wolfgang Babisch, a German researcher, has since the 80's investigated how the human body reacts to noise over time and how noise can be related to both cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer. The findings are striking and in 2014 Babisch pedagogically communicated how noise exposure leads to stress indicators that again can lead to risk factors and end up by being diseases [1].

Dr. Wolfgang Babisch, a German researcher, has since the 80's investigated how the human body reacts to noise over time and how noise can be related to both cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer. The findings are striking and in 2014 Babisch pedagogically communicated how noise exposure leads to stress indicators that again can lead to risk factors and end up by being diseases [1].

So – how loud is damaging noise then? How much noise (or how little) is too much?

In Denmark the Danish Cancer Foundation did a major research study from 2012-2017 to see if noise had any impact on developing cancer. The study left no doubt that noise can lead to breast cancer and non-Hodgkins lymphoma.

Just after this publication The Danish Ministry of Environment concluded that 500 Danes die every year because of traffic noise – because of diabetes, stress and cardio vascular diseases caused by noise. And The Danish Road Directorate concluded right after that 90,000 Danes out of a population of 5,600,000 are suffering from traffic noise. The publication was based on information from 7,000 people who are exposed to sound levels over 58 dB every day and night.

Hospital noise

If 58 dB seems to be a crucial limit on what the human being can withstand without developing risk indicators are we then home safe in hospitals? What are the actual sound levels in hospitals? A place where you go when you are already sick.

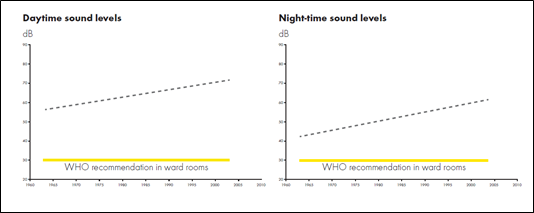

Hospitals and healthcare facilities are today really complex buildings – someone might say small cities and one thing is for sure: It is never totally quiet in a hospital. It works around the clock. Unfortunately, since the 60s the sound levels in general have gone up and the reason for this can be a combination of more people in the buildings, more equipment, more complex tasks – and in general more sound sources. Demographic changes also challenge the systems since we get older and older – and older people go to hospitals more often.

A study from 2005 reveals that both during daytime and night-time we see sound pressure levels way over the crucial 58 dB.[2]

WHO guidelines

In the above mentioned study not one hospital complied with WHO guidelines that recommend that average sound levels should not exceed 35 dB in most rooms in which patients are being treated or observed, since patients have less ability to cope with stress. Also WHO states that in ward rooms, the equivalent sound levels should be 30 dB and the noise peaks during the night should not exceed 40 dB [3] - which is also far away from the reality revealed in the study. You can always discuss if the WHO guidelines are obtainable in reality (30 dB is what you would have in a private bedroom) but the fact that WHO stresses low sound pressure levels in hospitals makes sense, because we are much more sensitive to sound and noise when we are sick.

The Outdoors

For thousands of years our bodies and brains have developed for the outdoors. If we compare the time we have lived outdoors as cave men to the time we have been living inside – we see a huge difference in time. Our hearing has not changed since we lived outside, and in this environment we needed our hearing to survive – if we didn’t react we would die. We needed both to react to the information in the sound (was it an animal or just the wind?) as well as the loudness to know whether to react, fight, flight or flee. When we are sick we seem to forget that just opening the door to a hospital takes us out of our comfort zone and all the stimuli can affect us as if we were out there in the cave – protecting our life. When we are sick our body and brain tell us to stay alert (we want to survive right?) and we are more sensitive to sound and noise than normal – and in hospitals this can be a challenge.

In nature we have no hard surfaces and no medical equipment – and we certainly don’t have alarms to wake up us all night. This outdoor environment is SO different from the environments we meet when we get sick and hospitalized and we are challenged simply because of that.

What does a hospital look like - if you look with your ears?

Large reflective surfaces. Technical equipment and phones. People everywhere. Moving beds and elevators. Complexity in action. As mentioned in the beginning of the article, hospitals are often small cities and when you are in the entrance hall of a hospital there is often no difference in sound between that and the entrance hall of an airport. The hard reflective surfaces and the big room volume affect the sound and make it build up. In the large corridors that often connects departments or as part of patient wards the geometry of the room allows the sound to propagate far away and it is not unusual that you can be part of a ‘halfasation’ (not conversation – because you only pick up half of it) more than 15 meters away. In the patient rooms where you rarely are alone, all that separates you from the person besides you is a thin curtain or fabric that lets every sound slip through. And finally, at the nurses’ stations alarms and machines adds just that little extra to the hospital cacophony.

This is the reality in many countries and especially in countries where room acoustic demands are lacking or simply are not serious enough. Luckily, we see changes in regards to this all over Europe these days and demands on both reverberation, sound propagation and speech clarity are finding their ways into building codes, standards and regulations.

The most amazing thing about it all is that it is NOT tricky to fix the room acoustic comfort in a hospital – we just need to mimic nature: Install an acoustic ‘sky’(absorbing ceiling) and ‘open widths’ for the sound to get away (absorbing wall panels).

Want to know more?

-

Read more the different factors you need to consider in order to achieve a good sound environment in healthcare premises. Here you also have the possibility to find information if you are considering to optimise a specific area within a healthcare facility.

-

Also listen to an interview with the German researcher Dr. Wolfgang Babisch, talking about his most important findings regarding how noise affects us.

References

NB. This article was originally published in Spanish at www.hospitecnia.com

[1] Wolfgang Babisch, Cardiovascular Effects of Environmental Noise Exposure, European Heart Journal 35(13), 2014

[2] Busch-Vishniac et al., “Noise Levels in John Hopkins Hospital”, Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Dec 2005, 118(6), p3629-3645

[3] Berglund et al., “Guidelines for community noise”, Technical Report 1999, World Health Organization